The Art of Intensive Reading

By Paul O’Connor

Arpad Szakolczai’s post a few weeks ago about the difference between open shelf and open access libraries underlines the role of presence – in this case the physical presence of books – in shaping how we read and think. It also reminds us that how we engage with books and writing is shaped socially, by factors like the institutions and technologies which produce and distribute them. This post explores another dimension of the same topic: the fate of what I call intensive reading in our digital age.

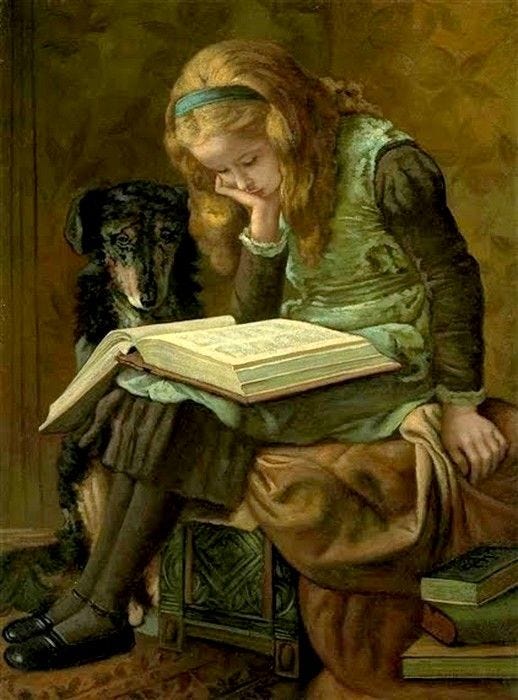

By intensive reading I mean the experience of being intellectually and emotionally immersed in a book for a lengthy period of time, and returning to it again and again, so it shapes how we experience the world, our thinking, our language, even our sensibility.

Anyone reading this post will be able to think of books which were for them, in the words of W.B. Yeats, ‘builders of my soul’. However it might seem strange to talk about the art of intensive reading. Surely this is something that comes naturally – one falls in love with a book, and reads it over and over?

Yet in our digital age intensive reading is becoming both rarer, and an art which increasingly needs to be cultivated and preserved.

What is Intensive Reading?

One way of characterising intensive reading is by contrast with other types of reading. Intensive reading is not what you do in the doctor’s waiting room, when having ten minutes to fill you open CNN on your phone to check if World War III has broken out in the Middle East today. Nor is it ploughing through a research article or monograph to extract information or summarise an argument.

For me, intensive reading typically occurs when seated comfortably in my favourite armchair, knowing I have several hours of undistracted reading time ahead of me, and a good book to fill it – perhaps a classic I have read many times before; perhaps a new novel I have been keeping for this moment; perhaps a volume of history or travel literature that will transport me to other worlds and other times. It involves reading slowly and contemplatively, savouring a well-expressed thought or happy turn of phrase, perhaps re-reading particularly important or striking passages. Moreover, it requires the presence of a physical book in my hand – preferably an old companion, a well-thumbed veteran whose weight and heft remind me of evenings spent reading in different places and times, the smell of whose binding perhaps recalls the second-hand bookshop in whose stacks I originally discovered it. Maybe one could read intensively using a e-reader like a Kindle: it is hardly imaginable one could do so on a laptop or a phone, distracted by multiple open windows and constant notifications.

In other words, intensive reading involves a particular kind of relaxed concentration, facilitated by the absence of intrusions and distractions, as well the perception that the book you are reading is worth giving your undivided attention. In such circumstances the world of the book is vividly present, as you let yourself be captivated and carried away into the imaginative or intellectual realm conjured by the author. You may even feel the presence of the author themselves – a meeting of minds across time and space.

Intensive reading of this kind is not a mere matter of cognitively absorbing information or concepts. It is what Arpad Szakolczai terms a ‘reading experience’, something which changes the reader and leaves a lasting imprint on their mind and spirit. We may be conscious of this change, as when we absorb some new idea or intellectual perspective. But often – especially if what we read is a work of fiction or poetry, or a historical or ethnographic account – it will work silently and at deeper levels of the mind, sensitising us to new aspects of reality, broadening our capacity for empathy or imagination, or subtly shifting our perspective through exposing us to novel dimensions of experience.

Those books which repay intensive reading are typically ones we will recur to again and again. Often, the most important ‘reading experiences’ are not singular moments of insight, the equivalent of being struck by a thunderbolt, but involve repeated readings of an author, absorbing a little more of their insights and perspectives each time, while contemplating and reflecting on them between readings. There is a particular pleasure to be found in returning to a favourite work after a few years absence, reading it with fresh eyes, discovering insights or ideas that had been hidden before, making connections with other works read in the time between.

It goes without saying that simply skimming a book, or reading it in a purely functional and instrumental spirit, cannot induce a reading experience of this kind. Only certain kinds of books repay intensive reading; moreover, the kind of relaxed but alert and engaged attention required for it is only possible in particular circumstances.

In my own experience, I undoubtedly gave more time engaged in intensive reading in my teens and twenties than today. Partly no doubt this is a matter of age: as the years pass it becomes harder to replicate the excitement of discovery which accompanied my first reading of Yeats or Nietzsche, Herodotus or Livy, Dickens or Shakespeare – an excitement captured by Keats in his sonnet ‘On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer’:

Then felt I like some watcher of the skies

When a new planet swims into his ken;

Or like stout Cortez when with eagle eyes

He star'd at the Pacific—and all his men

Look'd at each other with a wild surmise—

Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

Moreover, in one’s forties commitments to work and family naturally leave less time for absorption in books. But beyond these individual factors, a broader change in reading habits is being driven by technology.

Intensive and Extensive Reading

For most of the history of civilisation, books tended to be relatively rare and precious, so most reading was by definition intensive. If you only have access to a few books you will naturally tend to read them again and again.

This was reinforced by the fact that in many previous cultures a large portion – perhaps the majority – of books were religious or philosophical texts, which demanded (and repaid) repeated study. Repetitive, contemplative reading of religious texts has of course been an important spiritual practice in many societies, and not only Christian ones.

Even after printing became established, the number of books in circulation remained small by later standards. In eighteenth-century Britain, someone who was literate but not particularly wealthy might own a dozen or so books – a Bible and Book of Common Prayer; some volumes of sermons; the works of Horace or Vigil; a few volumes of the English poets; perhaps a novel by Defoe, Smollet or Richardson. If this was the extent of your library, you would naturally read most of the volumes again and again, until you had them almost by heart.

Several developments of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries in Europe expanded people’s access to books and reading material. Circulating libraries, for instance, brought a steady supply of new novels even to the inhabitants of country towns. The expansion of the reading public due to rising literacy and growing prosperity created a literary marketplace which supported a growing number of authors producing a constant stream of novels, poems, political and religious pamphlets and journalism.

A greater number and variety of books – as well as other printed materials, such as periodicals and newspapers – made a new pattern of reading possible. We can term this extensive reading. This is the style of the voracious reader who eagerly devours book after book, reads quickly, and delights in novelty. If one wished, it was now possible to be a constant reader and yet continually explore new material, never reading the same work twice.

In reality of course, most readers would find a personal balance between intensive and extensive reading. There would be favourite books and authors you turned to again and again, while also enjoying a variety of new books.

This kind of balance between intensive and extensive reading was the default until yesterday – when it was upset, like so many other things, by the internet.

Skimming and Scrolling

The internet replaces both intensive and extensive reading with a new pattern of skimming and scrolling. Skimming is when you skim over the surface of a text, rapidly taking in some of the main points, before moving on to something else or clicking through to another text via an embedded link. Scrolling is the process of rapidly scanning through search results, news sites or social media feeds.

The internet promotes skimming and scrolling because it offers a virtually limitless amount of written and recorded material, much of which is free, all of which is just a click or so away. No matter how important or engaging the text you are currently looking at, there is always something else to check out, which is potentially even more important or interesting. This effect is exacerbated as the embedded links in most articles or websites draw one’s attention away from the text even in the process of reading it. Browsing online, with a dozen windows open at once, a stream of notifications and alerts, and a maze of links leading from one article or website to the next, is about as far from the experience of intensive reading as you can get.

The internet has also changed the type of writing we are exposed to. It is dominated by ‘content’ – which can be defined as text which is designed to attract eyeballs and clicks rather than communicate something meaningful. Such content does not induce intensive reading, because it doesn’t repay it.

There is now a large amount of research on how the internet rewires our brains, literally changing how we think.

In his book The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains, Nicholas Carr describes how the internet physically reshapes the brain as it trains us to scan, jump from topic to topic, and consume information in small doses.

People tend not to read full articles on the web. Instead, they read the beginning, jump to the middle, and abandon the article before the end, becoming habituated to absorbing information in fragmented pieces.

We have also learned to externalise our memory to Google – but without a rich store of information and ideas in our memory, we are less likely to have original thoughts and ideas of our own.

Carr describes how in pre-internet times, during the prolonged, distraction-free reading of a book, people reflected on what they read, made their own connections, and developed their own analogies and ideas. Books fostered deep attention and thinking with discrimination.

But internet use makes it harder for people to focus for long periods. Habituated to the constant dopamine hits of clicking links and receiving replies, likes and shares, we become dependent on the constant stimulation derived from skimming and scrolling.

Skimming and scrolling reaches its logic culmination with generative A.I. Now you don’t even have to bother reading a book or article yourself to extract and summarise the main points, since Chat GPT or Google Assistant will do it for you.

Not surprisingly, evidence is emerging that the use of A.I. is associated with dramatic declines in cognitive function. A recent study from MIT – see https://arxiv.org/pdf/2506.08872v1 - comparing people who wrote an essay using ChatGPT with people who composed the essay without assistance from A.I. or a search engine showed the ChatGPT group had 55% reduced brain activity.

The bottom line: outsourcing your memory to search engines, relying on A.I. to do your writing and thinking for you, and habituating yourself to consuming information in disconnected fragments online makes you less intelligent. Who knew!

But the problem is not just technology. Schools and universities no longer train students in the deep reading of classic texts, but to rapidly scan and extract information from multiple sources and apply it to argue for their own (typically unexamined and ill-informed) opinions. Across journalism, publishing and academia the proliferation of online information and A.I. tools, and the constant pressure to increase ‘productivity’, has resulted in a collapse in standards and the proliferation of shallow, repetitive and meaningless publications.

Digital Solipsism

Past societies had their collective memory and cultural continuity destroyed by barbarian invasions, foreign conquest or environmental catastrophes. We’re doing it to ourselves with our prized technologies, the internet and A.I.

The effects are only going to get worse as the generations who grew up before the internet are replaced by those who have known nothing else. I count myself very lucky not to have had a home internet connection before the age of 19 – and even this was the old, slow, dial-up connection. It would be almost another decade before fast, reliable broadband made the internet a ubiquitous and inescapable presence.

The long, slow summer days and weekends of my pre-internet childhood and teens were a training ground in both intensive and extensive reading. Those were also the days before YA (young adult) fiction became a thing. Once I grew out of children’s books, if I wanted reading material it meant reaching for volumes on history and art from my mother’s shelves, or picking up cheap imprints of classic novels and poetry in bookshops around Cork City.

Anyone who has grown up with constant access to the limitless stimulation and information available online inhabits a different cultural universe. They have little opportunity to develop the habits of intensive reading many of us took for granted until yesterday.

There are many reasons why the switch from intensive reading to skimming and scrolling is profoundly damaging. Even more important than potential reductions in cognitive ability or ‘IQ’ is the way in which digital habituation, with its lowered attention span, makes certain kinds of intellectual and emotional experience less accessible.

The deep engagement with a book or author involved in intensive reading makes distant times, places and ways of thinking present in a way that watching a TV program or scrolling online cannot. Any genuine writer puts a part of themselves – often the best part – on the page. It is more than a metaphor or romantic conceit to describe the process of intensive reading as a communion of spirits or meeting of minds. Immersing yourself in a good book means participating, in at least some degree, in the experience and thought of the author.

By contrast, skimming and scrolling confines you to a bubble of currently fashionable and ‘right-thinking’ ideas and opinions.

There is much discussion today about online ‘filter-bubbles’ – virtual spaces where people with similar opinions congregate and have their pre-existing political viewpoints reinforced by others who share them. But the digital realm as a whole constitutes one massive filter bubble.

Our intellectual and spiritual ‘bandwidth’ is reduced. What is termed ‘onlife’ generates cultural shallowness and solipsism.

The Art of Intensive Reading

So we circle around the point with which I opened – intensive reading is no longer something we can count on to ‘just happen’, but an art which needs to be cultivated and preserved.

The first step is being aware of and reflecting on how technology is changing our reading habits, and what stands to be lost as a result.

Then we can try to ensure we have times that are free of digital distractions, in which we can once again have the experience of being utterly lost and absorbed in a book. This is not just a matter of being logged off, but can extend to deliberately setting aside specific times and places as dedicated to intensive reading. If we have a certain spot – a room or a chair – which we associate with absorbed and concentrated reading and thinking, and where we avoid browsing online, it will be easier to enter the relaxed yet focused state of mind characteristic of intensive reading.

But of course, not every book will repay the effort of intensive reading. So part of the art is actively curating our reading, sometimes rediscovering old favourites we have not read for many years, sometimes setting ourselves to read classic works we have not read before.

More broadly, there is a need to foster a culture of intensive reading in schools and in academia, in place of narrow functionalism and an obsession with ‘relevance’. As a society, we need to reclaim the idea that reading is not something purely instrumental, and not just a mode of entertainment, but what Foucault termed a ‘technology of the self’, and Pierre Hadot (suggestively) ‘spiritual exercises’ – a means of deepening our minds and spirits and opening ourselves to thoughts and experiences beyond the bubble of the present.