By Arpad Szakolczai

The 1790s, the decade of the French Revolution, was an extremely productive period for Goethe, both in terms of the quality and character of his works. The two phenomena of course were closely interrelated. Goethe was 40 at the outbreak of the Revolution, and so this event broke his life in two more or less equal parts, as he died in his early 80s. Like most “men of culture” of his times, and indeed of later times, at first Goethe was enthusiastic about the events. However, he soon changed his mind, and quite radically. It is noteworthy that while the evaluation of the Revolution by historians and social scientists, up to our own day, is almost univocally positive, the three most important classical-modern novelists, Goethe, Dickens and Dostoevsky, agree in their uncompromising condemnation of the violence and demagogy of the events.

The positive assessment of the events, and especially their iconic status in the French cultural-political memory, is something of a serious scandal. “The Marseillaise”, for example, which is the French national anthem, is a seriously problematic song, with its demagogic incitement to bloody violence – hardly better than the not only similarly violent but also literally apocalyptic “The Internationale”. It is not accidental that modern French history is full of particularly demagogic political leaders of highly questionable morals, crowned currently by Macron. For a much-needed reassessment of the French Revolution, see Camil Roman’s The French Revolution and Its Legacy: Leaping Democracy into the Unlimited, published just a few weeks ago.

Still, living through the events certainly stimulated Goethe’s creative powers. In the middle of the decade Goethe finished and published the first volume of his Wilhelm Meister novels, as well as Hermann and Dorothea, his most famous epic poem, while already in 1790 he published a fragment of Faust. However, in terms of affinities with the events, the perhaps two most important related publications are the 1794 poetic cycle Reynard the Fox, and the 1797 poem “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice”.

The former took up the most popular medieval Trickster tale, with the “crafty and self-seeking, yet curiously sympathetic fox” embodying cunning. He started writing it in 1792, in the context of his increasingly negative view of French Revolution, based on his own experience. The Revolution was appalling not only due to the violence it unleashed, but also its promotion of generalised irresponsibility, hypocrisy, endemic guile and cunning, leading to corruption and general degradation. Yet, at the same time, this also gave rise to grotesquely comic situations. All this would be repeated, in astonishing detail, with the Bolshevik Revolution.

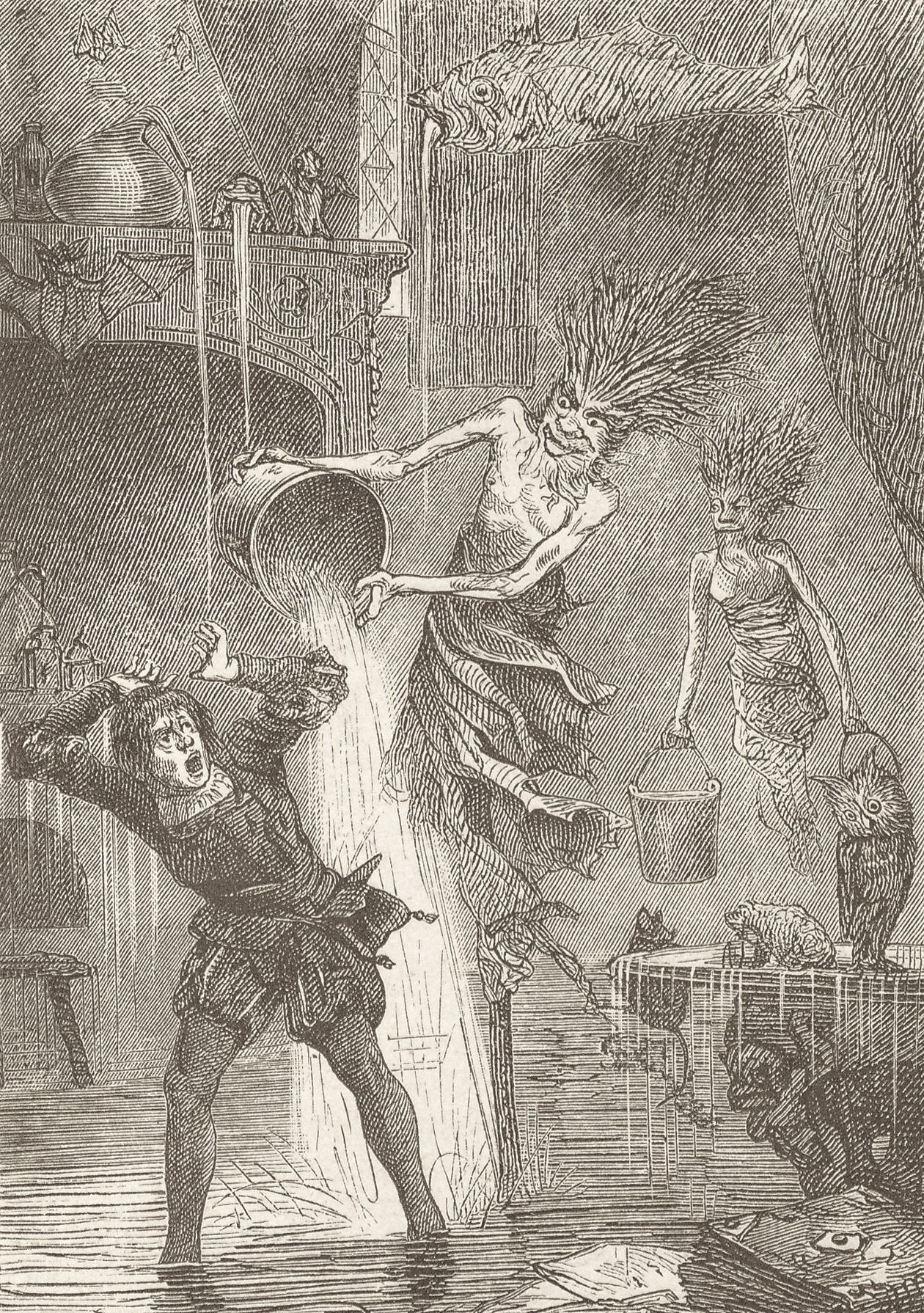

‘The Sorcerer’s Apprentice’ is significant because it shows how Goethe managed to perceive, on the spot, the eerie connections between the main modern revolutions: the political revolution, with its own madness and mayhem, reminded him of the similar character of the technological and scientific revolutions – and also the economic and mediatic ones.

The poem, attached at the end of this post, speaks for itself, so it does not require a long commentary – except, perhaps, a few sentences about its two English title words. The “sorcerer” of the poem (which in German is not a title word, though the protagonist is certainly present in the text), to be sure, refers to the Supreme Power – God, the Divine, or the highest deity. Goethe is not particular about the kind of religion and religious power it evokes, and makes no direct allusion to Christianity. This is all the more evident as – this should be known to everyone – Goethe evokes a single sorcerer, while Christianity is not a monotheistic religion, but is Trinitarian, following particular historical manifestations of such Supreme Power(s) and the history of their interpretation. It is not accidental that Isaac Newton, founding father of modern “science”, is anti-Trinitarian, and thus not Christian.

The “apprentice”, on the other hand, evokes the human side – technology and science, especially science, the “man of science”, the modern scientist who in his infinite folly and his mad pretence to discover the universal laws and “facts” of the “world” is on course to destroy the Earth and its Nature, our home. Some of this knowledge might indeed have a degree of universal validity, but it does not matter, or rather, this makes it all the worse: as while this knowledge is not sufficient to destroy the universe, it is more than sufficient, not in spite but due to its effective powers, to devastate the Earth and Nature, exactly because such scientific universalism ignores the specific features of our Nature and is therefore worse than sheer ignorance.

The environmentalists of our day often lament that we do not listen enough to the “scientists”. However, this only demonstrates their own folly and ignorance – which a previous blog already discussed in some detail – as “science” is only used to register the destruction for which it is itself responsible, and is thoroughly incapable of overcoming its own, limited perspective. Its main limit is exactly its universality, as it ignores, cannot help ignoring, the natural limitations of our own life and existence. Perhaps the folly of ignoring such limits is the ultimate truth of the famous Socratic ignorance.

Goethe’s hostility to technology and science is not confined to this poem. In the last act of Faust II, he goes as far as connecting technological process to human sacrifice, and not just as a metaphor; and his colour theory, the first spark of which he traces to Verdun, August 1792, and his participation in the Prussian campaign against revolutionary France, is a frontal attack on Isaac Newton, whom he outright accuses of committing crimes.

Yet Goethe’s judgment was on the spot concerning other two main modern revolutions as well – those involving the economy and the media. As regards the former, according to the distinguished St Gallen Professor of Economics Hans-Christoph Binswanger (1929-2018), the second volume of Faust offers a recognition of the magical-alchemic character of the modern economy (see his Money and Magic: A Critique of the Modern Economy in the Light of Goethe’s Faust). Regarding the latter, Goethe was hostile to the press, in particular to newspapers, which in a letter of 18 August 1792 he called his “most dangerous enemies”.

But let’s now turn to his words and the poem. And let’s hope that something like the conclusion of the poem will materialise in our lifetime – or, at least, in the time of our children’s children’s children.

The Sorcerer's Apprentice (1797)

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (Translation by Edwin Zeydel, 1955)

That old sorcerer has vanished

And for once has gone away!

Spirits called by him, now banished,

My commands shall soon obey.

Every step and saying

That he used, I know,

And with sprites obeying

My arts I will show.

Flow, flow onward

Stretches many

Spare not any

Water rushing,

Ever streaming fully downward

Toward the pool in current gushing.

Come, old broomstick, you are needed,

Take these rags and wrap them round you!

Long my orders you have heeded,

By my wishes now I've bound you.

Have two legs and stand,

And a head for you.

Run, and in your hand

Hold a bucket too.

Flow, flow onward

Stretches many,

Spare not any

Water rushing,

Ever streaming fully downward

Toward the pool in current gushing.

See him, toward the shore he's racing

There, he's at the stream already,

Back like lightning he is chasing,

Pouring water fast and steady.

Once again he hastens!

How the water spills,

How the water basins

Brimming full he fills!

Stop now, hear me!

Ample measure

Of your treasure

We have gotten!

Ah, I see it, dear me, dear me.

Master's word I have forgotten!

Ah, the word with which the master

Makes the broom a broom once more!

Ah, he runs and fetches faster!

Be a broomstick as before!

Ever new the torrents

That by him are fed,

Ah, a hundred currents

Pour upon my head!

No, no longer

Can I please him,

I will seize him!

That is spiteful!

My misgivings grow the stronger.

What a mien, his eyes how frightful!

Brood of hell, you're not a mortal!

Shall the entire house go under?

Over threshold over portal

Streams of water rush and thunder.

Broom accurst and mean,

Who will have his will,

Stick that you have been,

Once again stand still!

Can I never, Broom, appease you?

I will seize you,

Hold and whack you,

And your ancient wood

I'll sever,

With a whetted axe I'll crack you.

He returns, more water dragging!

Now I'll throw myself upon you!

Soon, 0 goblin, you'll be sagging.

Crash! The sharp axe has undone you.

What a good blow, truly!

There, he's split, I see.

Hope now rises newly,

And my breathing's free.

Woe betide me!

Both halves scurry

In a hurry,

Rise like towers

There beside me.

Help me, help, eternal powers!

Off they run, till wet and wetter

Hall and steps immersed are lying.

What a flood that naught can fetter!

Lord and master, hear me crying! -

Ah, he comes excited.

Sir, my need is sore.

Spirits that I've cited

My commands ignore.

"To the lonely

Corner, broom!

Hear your doom.

As a spirit

When he wills, your master only

Calls you, then 'tis time to hear it.

"

Would you agree that the core of the modern revolution is theological-political (concerning the relationship between the divine and the human)? A pertinent statement on "journalism": https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b2u5-MzKFvE